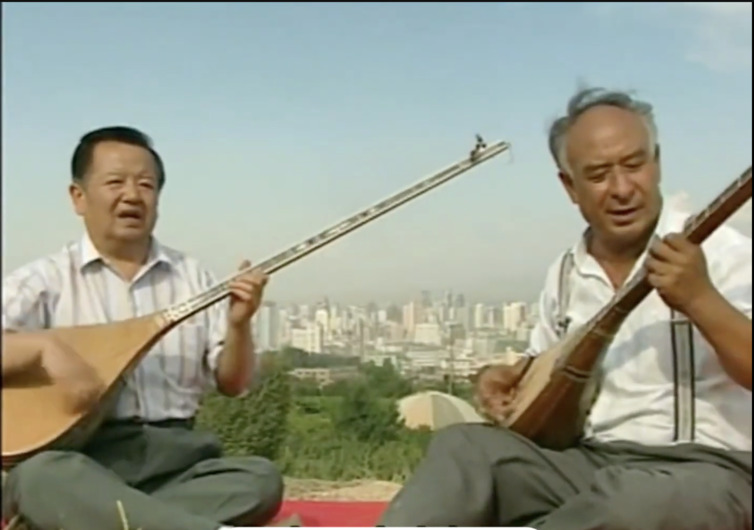

Photo courtesy: Abduweli Ayup

By Anne Kader

Language is a God-given gift to every nation, which we often take for granted. In the west, a person can exercise freedom of speech without the fear of being detained for one’s words.

Uyghurs, a Turkic people living in Uyghuristan (East Turkistan), are not enjoying these rights. It is practically forbidden for them to use their mother tongue publically or display Uyghur language signs in their occupied homeland.

Abduweli Ayup, an Uyghur language scholar in Europe, has paid a heavy price for promoting and maintaining the Uyghur language. One would consider it a human right for Uyghur parents to transmit their language and culture to their children. The Chinese regime grossly violates this right.

Abduweli found himself in trouble after establishing Uyghur language schools in his homeland in 2011. In 2013 he was detained and sentenced to 18 months in prison for alleged illegal fundraising for the schools.

Quenching a language is not a simple task. It requires an evil will to put a language out of existence. There can be attempts to control and manipulate its use, but as long as willing communicators in that language exist, the language will likely survive, alas in exile.

– Abduweli, what has kept you going after your release from prison?

Abduweli: I still remember when I was released on a Thursday morning, and I decided to stay in Urumqi for one day. The following Saturday, I was already teaching in Kashgar. Before my arrest, I had had more than four hundred students. Half of them had been waiting for my release. I began teaching in a Language Training Center established by a friend. Before my detainment, I had worked in a kindergarten and a language training center of my own. After my release from prison, I worked for a friend in his company. Paradoxically, all the students there were my former students. I also received many new students. I kept teaching till August 2015.

I had a problem: I didn’t have a place to live in Kashgar. My resident’s permit belonged to a Chinese city called Lanzhou. I was not allowed to live in Lanzhou either, because I was not born there. I was an Uyghur born in Kashgar. Eventually, the police placed a sign on my door saying: You are not welcome to live here, as your residence permit is in Lanzhou. You have a criminal record. You are not a safe person to live here.

I decided it was time to leave.

– How are you promoting the Uyghur language today?

I currently promote the Uyghur language in two ways: I teach Uyghur language courses. I also encourage other Uyghur teachers to teach Uyghur as a mother tongue wherever they live. Between 2016 and 2018, we had a network of sixty teachers and nineteen Uyghur language schools in different parts of the world. The third way is through my writings: I write for children and adults alike.

When my daughters were younger, we did ‘Uyghur language weekends’ during which we spoke in Uyghur only. I encourage other Uyghur parents to do similar things with their children. Some families have done so. My daughter has also invited other kids to join us, and they have later decided to follow our example. We want to encourage families to speak Uyghur at home.

Also, poetry is a brilliant way to learn and maintain the language. It is very rhythmic and easy to memorize. We like to recite poetry and spread our beautiful language.

– Is it challenging for Uyghurs to maintain their mother tongue in the diaspora?

Yes, we have challenges everywhere in the diaspora. We can request our children to speak Uyghur at home, but the problem is that their language basis is not very strong. Their Uyghur is a spoken language, which is never as strong as a written one. It does not contain sufficient vocabulary for deep thinking and self-expression. In exile, our children attend American, Turkish, or European schools. They learn to express their ideas in English or other languages. It is difficult for them to discuss more complex matters in the Uyghur language because they have never studied topics such as History or Science in Uyghur.

Photo courtesy: Abduweli Ayup

At home, we can speak Uyghur, but the topics revolve around everyday life, such as eating and hobbies. These are not enough to maintain the vibrancy of the language.

We do have Uyghur mother language classes, but our challenge is that Uyghurs live in many different places. There are three Uyghur communities in Turkey, whereas many other countries do not have Uyghur neighborhoods.

Even though we teach Uyghur to our kids two hours every week, they cannot use the language in their everyday surroundings, such as with their friends and peers, nor can they express their deep feelings in Uyghur.

Thirdly, we don’t have enough books. We had to leave them behind in East Turkestan, and we cannot bring them to where we live now. We would like to have more books in Uyghur and I encourage Uyghur writers to create and publish in our mother tongue. It can be challenging, as the task requires a professional team to publish the books: people with computing skills, graphic artists, and illustrators. As a network of sixty language teachers, we intend to publish books in Uyghur, for Uyghurs, and about the Uyghurs.

Many Uyghur writers who publish books in the Uyghur language do so at their own expense. They do not care whether the books sell or not: They want to do their part in keeping the language alive.

– Are there fears of assimilation among the Uyghurs in diaspora, and how are these fears addressed?

Yes, the Uyghurs are worried about assimilation. Many are also active in advocating for Uyghur rights, which is part of preventing assimilation.

– How, in your opinion, is the Uygur language connected to your Uyghur identity?

The Uyghur language is the essence of Uyghur identity. Language is the core of the culture. Language connects different generations, and it preserves culture through written works. If an Uyghur has forgotten his language or has not for some reason been able to speak it, it makes it challenging to partake in the Uyghur society.

– What do you think happens when a person is robbed of his/her mother tongue and forcefully made to adopt a foreign language instead?

If someone is robbed of their mother tongue, it equals to the person being robbed of one’s confidence. The mother tongue is the source of self-confidence. When I’m communicating in Uyghur, I feel confident, as the language is flowing from my heart. When I speak in English, I feel as if I am just imitating something: It is not the language to express the deepest feelings of my heart.

When someone forbids children to use their mother tongue, they rob their identity, dignity, confidence, and self-esteem. It leaves them feeling like second-class citizens, even if no one says anything. One can feel the gazes when one cannot speak the language as well as the others. This can be particularly traumatizing because Uyghur children also look different (from Chinese children), and they are easily recognized as Uyghurs.