The Art of the Bazaar: A Photo Essay

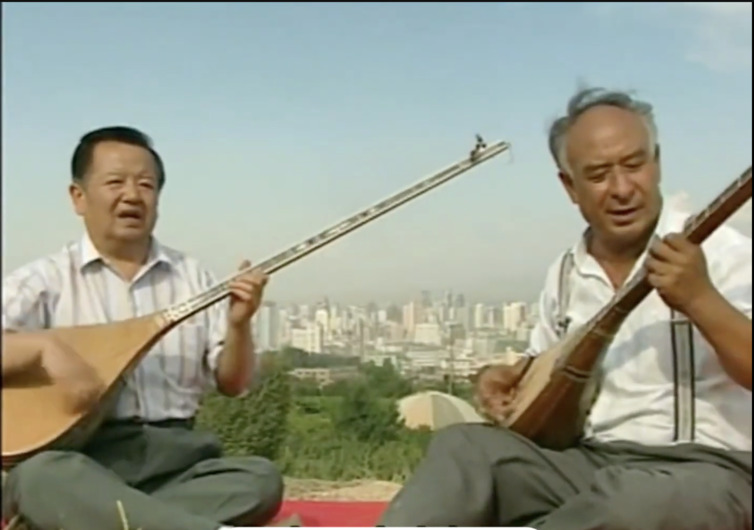

Every Friday Muslim migrant men fill the streets surrounding the mosque in the Ürümchi neighborhood of Black First Mountain (Heijia Shan). They come to pray. After the noonday (zohr) prayers and straining to hear the weekly message from the imam, they tuck their rugs under their arms and buy their meat for the week. Thousands come, Uyghurs from the countryside who are in the city working as day laborers in demolition sites or hawking goods on the streets, to perform their ritual ablutions and stroll through one of Ürümchi’s last remaining bazaars. For centuries bazaars and mosques have been a linked ritual space for Muslims in Chinese Central Asia.

After praying, Muslim migrants to the city tuck their prayer rugs under their arm and stroll through the Friday bazaar.

Following the protests and subsequent violence of 2009, this neighborhood was one of the first areas targeted for urban cleansing. The degraded housing of the nearly 10,000 Uyghur migrants in the neighborhood was leveled. Each family was registered or forced to leave. Those who were not expelled from the city were offered partially-subsidized housing in newly built 20-story apartment buildings as compensation for the loss of their former homes. In the summer of 2015 only two “nail houses” (dingzihu) owned by elderly Uyghur sheep farmers from Kashgar remained standing. By the autumn of that year they were demolished as well.

The “nail houses” of Uyghur sheep farmers in the Ürümchi neighborhood of Heijia Shan

As a result of the demolition of Uyghur migrant housing, the neighborhood has become one of the centers of recycling in the city. Recent Han migrants from Anhui and Henan have set up fiberglass, cardboard and glass sorting spaces. They traveled thousands of kilometers to the Central Asian frontier because they heard that work for Han settlers pays well and the rent is cheap so far from the population centers of the nation. For many of them, farming back in their home provinces is no longer a tenable livelihood. On Fridays their work slows, since the Uyghur scrap-gathers who supply them are taking time off to attend the mosque.

Han migrants from Henan secure a load of washing machines to be sent to a recycling center in the Uyghur neighborhood of Heijia Shan.

Uyghur second-hand furniture and appliance sellers have built ad-hoc warehouses on the margins of the demolition zone. Next to new walls and rutted dirt pathways they arrange their wares for migrants who come for the Friday market. Camels and sheep are slaughtered and eaten — roasted on skewers over open coal-fired grills — along the same pathway. Men gather in clumps and discuss the merits of kidney medicine, the newest smart phones, and the latest news.

A camel’s head advertises the freshness of the meat for sale at the market.

Plain-clothes police also come looking for wanted men every Friday — they scan the crowd looking for who has come to pray. Since the mosque at the center of the bazaar is known to be preferred place of worship for migrants and the homeless Muslims of the city, it is watched more closely than other mosques in the city. Every few weeks warehouses and restaurants are closed due to a lack of official permits, but still the bazaar goes on in the rubble of Ürümchi’s past.

Plain-clothes police also come looking for wanted men every Friday.

This photo-essay first appeared in the 2015 Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellow Photo Essay Competition.