By Ihsan Umun

Since 2016, the Uyghur region has generally been closed to Turks, but it was partially opened between 2024 and 2025.

During the period from 2016 to 2024, there are official statements from the Turkish side indicating that China did not allow Turkish delegations into the region and even actively blocked them. The then Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu announced at the end of 2022 that China had blocked the Turkish ambassador’s visit for five years. Similarly, a Turkish delegation trip planned in 2019 (about 10 people from various institutions) did not take place due to repeated postponements by China.

Under pressure from the West regarding the Uyghur issue, China had previously invited delegations from the Middle East, Africa, and Central Asia (organizing more than 100 visits), but none of them included Turkish representatives.

In June 2024, Hakan Fidan visited the region as “the highest-ranking Turkish official to visit East Turkistan since 2012.”

Following Hakan Fidan’s visit, China began organizing planned and structured tours of East Turkistan.

Turkish Delegations as Tools of Chinese Propaganda

In August 2024, China organized the first group visit for Turkish journalists to the Uyghur region as part of a media tour specifically arranged for them. This visit was part of China’s strategy to “tell the Xinjiang story well” (讲好新疆故事). The tour, funded by public diplomacy and propaganda units affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, included journalists such as Mustafa Birol Güger from Cumhuriyet, İbrahim Varlı from BirGün, Erdal Emre from Yön Radio, Tunç Akkoç from Harici magazine, and Adnan Bulut from ANKA News. They visited centers like Urumqi and Kashgar.

Participants toured limited areas under the guidance of Chinese official guides, visiting pre-selected “model schools,” “model factories,” and “cultural centers.” After the tour, the group published content favorable to China, claiming that “genocide allegations are baseless.”

Between September and October 2025, another group of left-leaning Turkish journalists visited the region at China’s invitation. This group included Merdan Yanardağ, Ümit Zileli, Mehmet Ali Güller, Yavuz Selim Demirağ, Erkin Öncan, Haluk Hepkon, Yavuz Alogan, and Zeynep Gürcanlı. China’s target audience this time was again “secular, nationalist, and leftist circles.” Reports and videos shared after the visit emphasized statements such as “China is successful in combating terrorism,” “Uyghurs benefit from economic prosperity,” and “the region has become safe.”

In 2025, CNN Türk reporter Büşra Arslantaş and cameraman Caner Kınacı conducted a one-day Urumqi visit at the end of October at the invitation of the Chinese Embassy in Ankara. Arslantaş’s reporting was somewhat more balanced, making references to China’s repressive policies in the region.

Another visit in November 2025 involved a group from the AK Party Youth Branches being taken to China.

This was part of China’s “soft power” strategy targeting the conservative youth base in Turkey. Although official statements framed the visit as “for friendship and cultural exchange,” it continued the pattern of ignoring the Uyghur issue and promoting Chinese propaganda.

On November 6, Turkey’s Ambassador to China Selçuk Ünal met in Urumqi with Party Secretary Chen Xiaojiang and Regional Chairman Erken Tuniyaz. Ambassador Ünal highlighted “Xinjiang’s economic and social development achievements,” supporting China’s narrative. He also raised security cooperation and counter-terrorism issues, aligning with the framework legitimizing China’s policies in the region. Calls to increase trade and investment were presented in ways that reinforced Chinese propaganda.

Most statements from these delegations were favorable to China, supporting slogans such as “there is no genocide, only education and development.” China published this content in its own media to convey its message to domestic and international audiences. While Uyghurs were expecting independent delegations from Turkey to investigate genocide claims, dozens of visits served as material for Chinese propaganda instead.

The Turkish Left Failed the Uyghur Test

Despite the Uyghur issue being important for influencing the government’s base and highlighting ideological contradictions between nationalism and political Islam, opposition journalists did not direct comprehensive criticism at the government. In the Turkish left, the issue is generally not perceived in this way. In fact, some factions’ tendency to align with the government on the Uyghur issue confirms suspicions that China’s influence on Turkish leftist circles may be stronger than expected.

The Turkish left is accustomed to seeing the Uyghur issue as a right-wing matter. Unlike leftist circles in the West, the Turkish left approaches the issue with bias, linking it to political Islam and nationalism.

Moreover, nationalist opposition’s anti-Western stance oddly translates into sympathy for China. Some believe that by praising China, they can reinforce the perception that they hold a strong position against Western imperialism; some even think that to hate the West, they must love China.

Those in Turkey demanding human rights, democracy, and press freedom against an increasingly authoritarian political Islamist regime visited the Uyghur region and returned repeating the propaganda of one of the strictest totalitarian regimes in the world.

What is the difference between authoritarianism from political Islam and a single-party socialist dictatorship? By valid standards, dictatorship is dictatorship regardless of ideology. Genocide and violations are genocide and violations no matter who commits them.

I do not believe the leftist journalists visiting China met before or after with Uyghurs in detention camps, Uyghur activists, or intellectuals.

They gave the floor not to the victims but to the perpetrators and chose to promote their propaganda. They did not visit detention camps, speak to Uyghurs without Chinese supervision, ask about missing Uyghur journalists or detained intellectuals, attend schools where Uyghur-language education is banned, or speak with women forced into abortion or marriage with Han Chinese.

They praised China’s economic engagement in the region but said nothing about how much Uyghurs actually benefited. Either they made no preparation or did not want to check the real data.

They instrumentalized journalism to facilitate a totalitarian regime’s propaganda and normalize genocide.

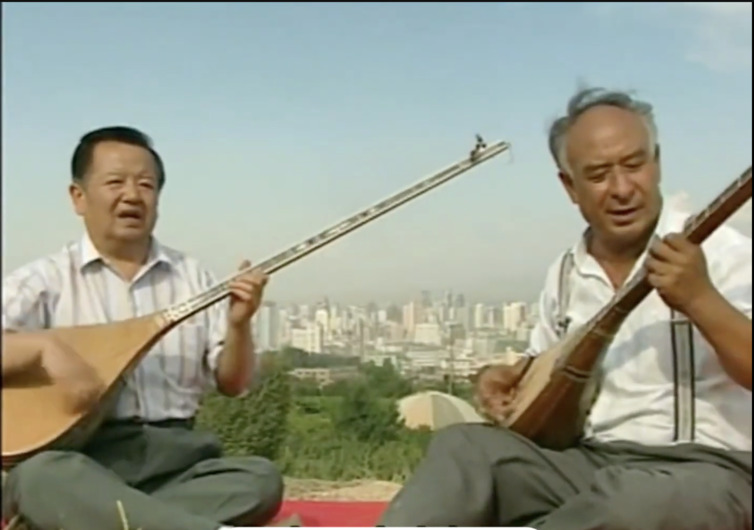

The Uyghur Turks

The Uyghur issue is not an ideological or pro-Western political matter; it is a question of human rights and democratic rights.

If visitors expected a Middle East-style war zone, it must be clarified: no one has ever claimed that. The situation in the Uyghur region is not a genocide carried out with guns and cannons.

East Turkistan is under maximum state control, monitored using the latest technologies, representing one of the world’s most extreme examples of surveillance.

We are talking about a systematic, planned genocide executed with the full combination of state apparatus in a dystopian reality constructed by the Communist Party. Without investigating it through real journalistic research, it is impossible to fully grasp the reality merely through visits.

From the staged scenes shown to delegations to the institutions they visited, everything (family, demographics, media, education, politics) is planned and executed in detail by the state. Understanding the actual situation requires more than just touring sites guided by state officials.

It is truly saddening that people who have never sat and talked with a Uyghur in their lives use the painful realities of Uyghurs to “hate the West” or “please China.”

What about the Turkish right?

The situation is somewhat complex. Although the Uyghur issue is seen as a “national cause” for Turkish nationalist circles, the government’s stance softened as relations with China developed. During the harshest implementation of genocide policies (2016–2022), the government took no concrete action against China. Ankara repeatedly emphasized that the Uyghur issue should be seen from a Turkish perspective—though what that perspective entails is still unclear. This was effectively a reference suggesting the Uyghur issue was Western propaganda.

This time, the AK Party opened the door to China for the conservative base. The AK Party Youth Branches group praised China’s “hospitality” and “economic success” on social media after their visit.

They managed to visit the Uyghur region without making any statements about the Uyghurs.

During the November 6 meeting, Ambassador Ünal’s remarks revealed the government’s alignment with China and avoidance of a critical stance on the Uyghur issue. Highlighting “Xinjiang’s development achievements,” emphasizing security cooperation, and calls for trade support China’s official narrative.

However, some positive outcomes occurred during right-wing visits.

CNN reporters were able to travel briefly in the region without state supervision, and their reporting attempted more to reflect reality than the organized staged scenes.

In June 2025, Taha Kılıç conducted an approximately eight-day trip and published his observations in a book titled In the Footsteps of the Lost Geography: East Turkistan Travelogue.

Although the government changed its stance on the Uyghur issue, right-wing journalists and writers maintained sensitivity. Even if criticized for acting under nationalist and religious impulses, at least they tried to remain as objective as possible in their journalistic work instead of promoting Chinese propaganda.

China’s Diplomatic and Media Strategy: Legitimacy Through Turkish Representatives

China uses these visits not only for domestic audiences but also as a tool of international propaganda. Programs coordinated by the Chinese Embassy (Ankara) and the Istanbul Consulate were organized through the Turkey-China Friendship Foundation. Content produced after the visits was published by major Chinese media outlets (Global Times, CGTN, Guangming Daily) under headlines such as “Turkish journalists saw the truth.”

These publications strengthen China’s arguments internationally. It is evident that China amplifies propaganda heavily through these publications. Positive remarks by Turkish journalists are reproduced in Chinese media as “independent testimony.” China presents Turkish representatives as “neutral observers from a democratic country,” producing the argument that “even the Turks saw and approved.”

Additionally, these visits aim to influence Turkish public opinion and shape perceptions of the Uyghur issue.

Debates in Turkey over sending delegations to the alleged genocide region, ongoing for years, ended up harming Uyghurs. No independent institutions or experts on the Uyghur issue were included. Despite a large Uyghur diaspora in Turkey, no intellectuals or camp survivors were consulted.

The visits were one-sided, serving propaganda and “whitewashing genocide.”

Uyghurs who once hoped for independent Turkish delegations ended up deeply disappointed. The consensus in the Uyghur diaspora is that Turkish delegations visiting the region sent a far worse message than if they had not gone at all.

İhsan Ismail is a Paris-based Uyghur reporter, editor, and analyst with a background in sociology and French studies. He writes for the newly founded Uyghur-language media outlet, the Uyghur Post. A graduate of Akdeniz University in Turkey (2020), he has reported for Radio Free Asia and written for Turkish outlets such as Medyascope, Gazete Duvar, and Serbestiyet. His work spans journalism, analysis, and literature, with poems published in Uyghur anthologies. İhsan writes in Uyghur, Turkish, and French.